|

Edinburgh

The Castle

|

The Great Hall, formerly

the castle's banquet hall

Basket-hilt swords

and battle axes

|

Clockwise from top left :

(1) western defenses

and new barracks

(2) the castle from Johnstone Terrace

(3) the castle

entrance

(4) esplanade to the castle entrance |

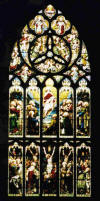

Scottish Monarchs

and Coats of Arms

The Reformers

and Coats of Arms

|

|

This ancient fortress stands as a sentinel, guarding the city and

giving silent witness to the tragedies and triumphs, the drama and intrigue, and

the poverty and riches of centuries of Scottish history. One pair of stained

glass windows in the Great Hall bears the names and coats of arms of Robert the

Bruce and other Scottish monarchs. In another are Scottish

reformers, most of whom were martyred for the faith.

The

high basalt rock upon which the castle stands was the site of a Bronze Age hill

fort. During the Roman occupation, it was a thriving settlement. By the eleventh

century, it was firmly established as a principal Scottish royal residence. The

earliest surviving part of the castle was built in the same century by David I.

During its 1,000-year history, the castle has been attacked, damaged, and rebuilt a

number of times. In the sixteenth century, Oliver Cromwell established a

permanent military base on the grounds; he, who despised the religious passions

of the Reformers, also cared nothing for the aesthetic and historic features of

Edinburgh Castle. His army destroyed and erected buildings at the castle in a

manner which evidenced this disregard, creating something of a conglomeration.

In the

nineteenth century, fortunately, the re-emergence of a Scottish national

identity led to a change in emphasis at Edinburgh Castle. Sir Walter Scott

applied for and was granted permission to look for the Scottish Honours ~ the

sixteenth century Scottish Crown regalia consisting of a crown, scepter, and

sword ~ which had been missing since about

1707. He discovered them in the castle, exactly where they had been hidden

over a century earlier. They were placed on display, and the Great Hall

subsequently was restored. In 1923, the Scottish National War Memorial was

built, and the main garrison of the British army left the castle. Finally,

in 1996, Scotland's Stone of Destiny was returned to Edinburgh Castle from

Westminster Abbey, to which it had been "exiled" seven hundred years earlier. A

plain slab of sandstone, the Stone reputedly is the seat on which the ancient

Scottish kings were crowned. Today, the Stone of Destiny and the Honours

of Scotland are on display in the Crown Room of Edinburgh Castle.

Photographs are not permitted.

There was so much more of the castle to enjoy, but we

were spending only a day in Edinburgh and had yet to see St. Giles and

Greyfriars.

St. Giles Cathedral

| |

|

|

|

|

|

While a parish church

has been in Edinburgh since about 854 A.D., St. Giles Kirk was built in the 12th

century. A 1385 fire destroyed most of the structure, with four massive

pillars in the center of the building possibly being all that survived.

Rebuilding began and continued almost unabated until the early 16th century.

In the 17th century, St. Giles was declared a cathedral by Charles I and again by

Charles II, a status it lost when Presbyterians gained control of the church,

though the name is in use today. St. Giles

is generally considered the mother church of Presbyterianism.

During the Reformation, many changes were made to the interior

- some publicly

and some in secret - owing to significant differences in doctrine. One

example is that Presbyterians hold that all believers are saints, meaning set aside for

God's holy purposes, and that no saint is able to grant favor with or access to

God. For that reason apparently, a statue of the venerated St. Giles was removed in the night by a person or

persons unknown and has never been recovered. It seems ironic that there

stands in the church today a statue of John Knox, the reformer whose work gave

birth to the Presbyterian Church. The difference, however, is that neither Knox

nor any other reformer was venerated, nor were any regarded as holding an elevated status

before God. (The statue standing outside St. Giles is of the Fifth Duke of Buccleuch.)

John Knox preached his first sermon at St. Giles on 1 July 1559.

He was described by his clerk, John Bannatyne, as "the light of Scotland, the

comfort of the Church ..., the mirror of godliness, a

pattern and example to all true ministers, in purity of life, soundness of

doctrine, and boldness in reproving of wickedness; one that cared not for the favour

of men, how great soever they were." A less partial man, Principal Smeton, also spoke of Knox in glowing terms: "I know not if ever so much piety and

genius were lodged in such a frail and weak body. Certain I am, that it will be

difficult to find one in whom the gifts of the Holy Spirit shone so bright, to

the comfort of the Church of Scotland. None spared himself less in enduring

fatigues, bodily and mental; none was more intent on discharging the duties of

the province assigned to him. ... Released from a body exhausted in Christian

warfare, and translated to a blessed rest, where he has obtained the sweet

reward of his labours, he now triumphs with Christ."

Another prominent name associated with St. Giles is

that of Archibald Campbell (1607-1672), First Marquess and Eighth Earl of

Argyll. When religious principle came into

question, titles, lands, and power meant nothing to him. Firmly believing

that Christ, and not the king, was sovereign over the church, he signed

Scotland's 1638 "National Covenant," a response to King Charles I's attempts to

rule the church in Scotland. The Covenant emphasized Scotland's loyalty to the

king, insofar as the king did not infringe upon religious faith and freedom, and

it declared that any attempt to move the church toward Catholicism would be rejected. Campbell

was eventually left both

penniless and powerless, and he was charged with conspiracy in

the murder of Charles I because he had worked for a time with the Cromwellian government.

Since Cromwell had orchestrated Charles's death, Campbell was declared guilty of the conspiracy as well. When a sentence of death was pronounced and

his wife cried out, "The Lord will pay them back for this!" he quietly

admonished her: "Control yourself, Dear. Truly, I pity them. They don't know

what they are doing; they may shut me in where they please, but they cannot shut

God out from me. For my part, I am as content to be here as in the castle, and

as content in the castle as in the Tower of London, and as content there as when

at liberty, and I hope to be as content on the scaffold as any of them all." Archibald Campbell, Covenanter, stood on the scaffold on 27 May 1661 and spoke

calmly to those around him. A physician checked his pulse and found it steady. And then, he was beheaded.

The monument to his memory, above, was later placed in St.

Giles. On it are inscribed these words: "I set the Crown on the King's

Head. He hastens me [by execution] to a better Crown than his own."

While Campbell was memorialized at St. Giles, it

was in the kirkyard of another, more modest kirk that the Covenant had been

signed. A walk of a few blocks brought us to ...

Greyfriars Kirk

|

|

|

|

The first church built in Edinburgh after the Reformation,

Greyfriars opened in 1620. In 1638, the first National Covenant was publicly read and signed in

its kirkyard. King Charles I wished to rule not only Scotland

but also, through bishops whom he had appointed, the church. He

required that all kirks follow the English Prayer Book in worship.

The Covenant, co-authored by Archibald Johnston of Warriston and Alexander Henderson, emphasized loyalty to the king but demanded religious freedom. |

The Covenant was signed immediately

by leading individuals such as Archibald Campbell, whose memorial was

built in St. Giles, and the following day by

the clergy and burgesses of Edinburgh. Afterward, copies were circulated

throughout Scotland, and 300,000 believers eventually signed the historic

document. Lord Cromwell, who at first had pretended to sympathize

with the Covenanters, later viciously opposed them. He placed his army in

Greyfriars Kirkyard and made it a prison. In 1679, about 1,200

Covenanters were confined in the open air and given only water and four

ounces of bread each day. Many died while others were either

executed, sent abroad as slaves, or eventually freed upon signing oaths of

allegiance. Over the course of the century-long Presbyterian

struggle, some 30,000 Scots died for their faith.

Contemplating

the persecution and suffering of thousands who did nothing worse than

resolutely hold to their faith, I thought how easily I sometimes grumble

over the smallest inconveniences of life. I left Greyfriars with no small amount of reflection,

and we drove

north of Edinburgh to have dinner at a different kind of historic spot.

Queensferry

Hawes Inn on the Forth River

At Queensferry, the

Forth River flows into the Firth of Forth, dividing South Queensferry

from the town proper. Facing the river is Hawes Inn, a favorite

haunt of author Robert

Louis Stevenson (1850-1894). Stevenson stayed often in room 13

and, according to local tradition, planted the yew tree that still

grows on the grounds. He spent long hours at a desk at the window, where he watched the great

sailing ships come in from the sea. There, inspired by the scene before him, he wrote a major portion of

his novel "Kidnapped". Stevenson was also the author of "Treasure Island", "Dr. Jekyll and Mr.

Hyde", and other works.)

The host at Hawes Inn was very gracious, showing us around

and apologizing that we could not visit room 13 as it was then

occupied. Our waiter was very cordial, and the food was

delicious. We thoroughly enjoyed our time at the Inn and would

gladly return.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

If you came from the Bed and Breakfasts page,

use your

browser's back button to return to that page.

If you came from a search, click here to begin at the

beginning:

Home

Contact

Copyright 2018 · Loretta Lynn Layman · The House of

Lynn |