|

Centuries of Scotland's history have been colored

"We

fight not for glory, nor for wealth, nor honour Robert the Bruce, King of Scots, planted his standard in the fields of Bannockburn on 23 June 1314. Eight thousand starving Scottish patriots rallied to his side, defying an English army of twenty thousand and vanquishing the oppressor, Edward II of England, in two days of fierce battle. Bruce, the warrior king, inspired an entire nation. Seven years after their great victory, faced with continuing threats of English invasion, Scots gathered at Arbroath on 6 April 1320 and declared, “... as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.”

"Scots wha

hae wi' Wallace bled, Scots wham Bruce has often led,

Wha would

be a traitor knave, wha can fill a coward's grave,

By

oppression's woes an' pains, by your sons in servile chains, Robert Burns

Culloden

The English victory at Culloden was hardly one of which to boast, and the behavior of the victors after the battle's end was appalling. The English used their muskets as clubs to dash out the brains of the wounded and sprinkled one another with Scottish blood. Then, once sated with blood, they casually dined upon the field where the dead still lay. In the 1820s, descendants of Highlanders who had died at Culloden placed rough memorial stones where various clans had fallen and were buried in mass graves. In addition to stones for the MacDonalds and other clans is a stone where many fallen highlanders whose families and clans were unknown lie buried together. In 1881, Duncan Forbes of Culloden erected at Culloden the large cairn seen above to memorialize all the Highlanders who had fallen. It includes a plaque which reads ...

"The Battle of Culloden was fought

on this moor 16th April 1746. After Culloden, everything about the Highland way of life was banned - the claymore, the bagpipe, and even the wearing of tartans. While one may lament the end of a way of life and abhor the brutality which which the Highlanders were treated, it was providential that they lost this, their last great battle for Scotland. Their would-be sovereign would have imposed on the entire nation a single religion. Fortunately, the ban on tartans was lifted in 1782, and in 1843 Queen Victoria appointed the first "personal piper to the Sovereign" of Great Britain. Today, Scotland again has her own Parliament to govern domestic affairs, and it is hoped that one day the political battle for full Scottish independence may be won.

I returned

to the fields of glory

In the great

glen, they lie a-sleeping,

See the tall

grass is there a-waving

March no more, my soldier laddie, Author Unknown

In his too brief lifetime, the Bard of Scotland wrote hundreds of heroic, romantic, or humorous songs and poems about his native land and people. The best known, of course, is "Auld Lang Syne." The most stirring, however, must be "Scots Wha Hae," which celebrates the valor of the Bruce and his Scots at Bannockburn. Burns himself gives an account of the inspiration for the song : I am

delighted with many little melodies which the learned musician despises as

silly and insipid. I do not know whether the old air Hey tutti

taittie may rank among the number; but well I know that with Frazer's

hautboy* it has often filled my eyes with tears. There is a tradition

that I have met with in many places in Scotland that it was Robert Bruce's

march at the Battle of Bannockburn. This in my yesternight's evening

walk ... warmed me to a pitch of enthusiasm on the theme of liberty and

independence, which I threw into a sort of Scottish ode fitted to the air

that one might suppose to be the gallant Royal Scot's Address to his

heroic followers on that eventful morning. Robert Burns dearly loved his Scotland, and was so loved in return that the village where he was born began planning its monument to him a mere seven years after his death. Within five years more, sufficient funds were raised that construction could begin on his birthday in 1820. Finally, the monument was opened to the public in 1823. It is now surrounded by the lovely Burns National Heritage Park, which spreads over several city blocks and includes gardens, a museum, a 16th century church, and the 1757 cottage where Burns was born. For more about Burns's birthplace and its Brig O' Doon, visit Romantic Alloway.

Covenanter Martyrs

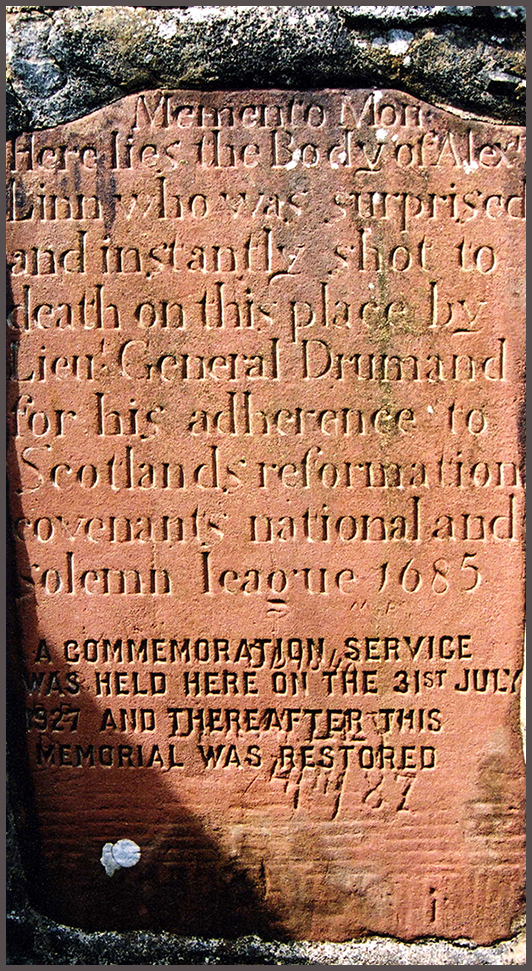

Alexander Linn Galloway is a land of both beauty and starkness. It is also, like most of Scotland, a land of both tragedy and triumph. Seeking a 300-year-old tomb, we drove the narrow, unpaved Southern Upland Way and hiked up the rocky, sometimes boggy moor of Craigmoddie Fell. The place was described in the 19th century by Rev. William Mackenzie as "a bleak, romantic spot". We looked for the stone wall enclosure that Ranger Mearns had told us surrounds the grave. Arriving at the first structure that caught our eye, we saw that it was an ancient, stone sheep pen. Had it belonged to the man whose grave we sought? We headed back down a bit and looked up in a slightly different direction. There was something else ... We walked toward it, hoping it was the object of our quest ...

When Linn's lifeless body was found, he was buried on the spot where he had died and the place was marked by a memorial stone. Over the succeeding 300 years, six memorial services were held at the tomb, the stone enclosure was built, and two additional, commemorative gravestones were added. The last service at Linn's tomb ~ 1985 ~ marked the 300th anniversary of his death.

On that spring day in 1685, what words of God were last on the heart and mind of Alexander Linn as he read the Word? What promises ushered him into his heavenly home as he left his earthly abode? Inside his tomb's enclosure, a rose is growing. On the hills around, sheep still graze.

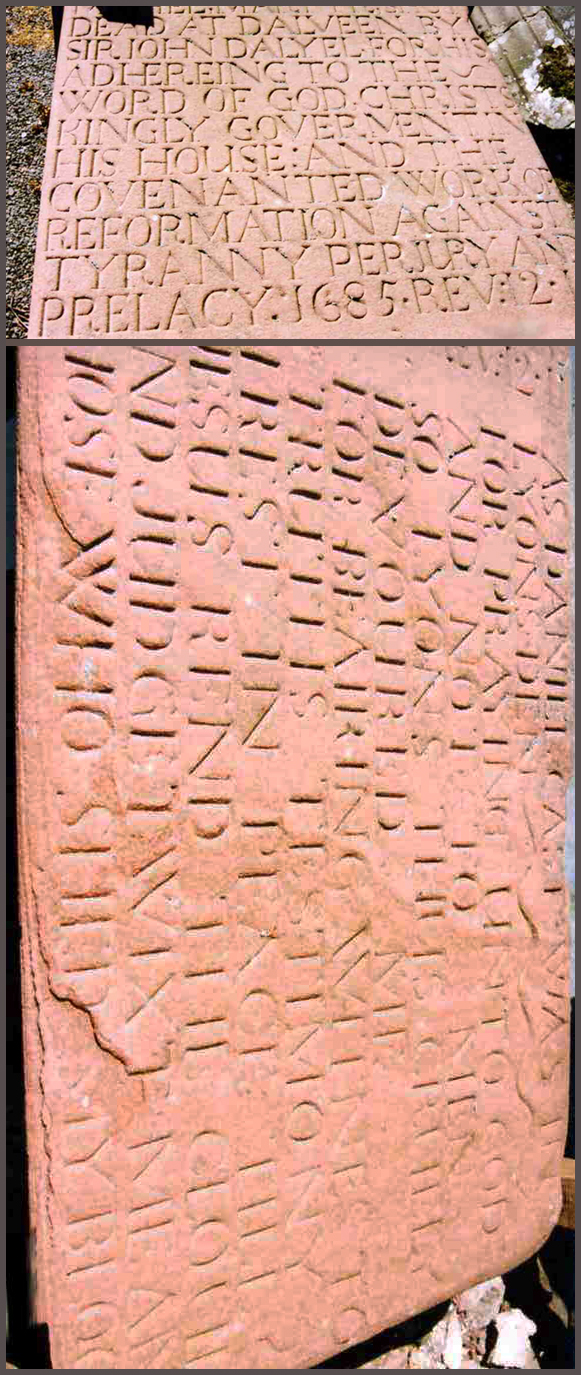

Daniel McMichael In the village of Durisdeer, on the western edge of the Lowther Hills in Dumfriesshire, is a fine stone kirk built by the first Duke of Queensberry in the late 17th century. The Duke and Duchess both are buried in the kirkyard, but the grave pictured here is that of a martyred Covenanter. His epitaph consists of two parts on a single stone, the first inscribed in one direction and the second perpendicular to the first. The first records the place, cause, and year of his death, along with a Bible reference. The second delivers a striking message :

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||