|

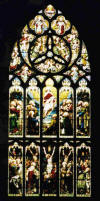

St. Giles Cathedral Auld

Kirk Alloway Kirkmabreck

St. Michael's

A parish church

has existed in Edinburgh since about 854 A.D. St. Giles was built three centuries

later. In 1385, a fire destroyed most of the structure, with four massive

pillars in the center of the building being all that survived. Rebuilding began and continued almost

unabated until the early 16th century.

It was declared a Catholic cathedral by Charles I and again by Charles II, a status it

lost when Protestants gained control. During the Reformation, many changes were made to the interior ~ some publicly

and others in secret ~ owing to significant differences in doctrine. For

example, Protestants hold that all believers are saints, meaning set aside for

God's holy purposes, and that no saint is able to grant special favor with or access to

God. For those reasons apparently, some person or persons unknown removed a statue of St. Giles in the night.

It has never been recovered. It is doubtful that John Knox would have

approved of his likeness eventually being erected by a later generation.

The kirk, still called St. Giles Cathedral, is generally considered the mother church of Presbyterianism. The statue standing in the square outside St. Giles is of the Fifth Duke of Buccleuch. More images can be

seen at: John Knox (c. 1514-1572) - Knox brought the Reformation to Scotland in the early 16th century and thereafter was exiled for about 20 years. He returned and preached his first sermon at St. Giles in 1559. He was exiled again in 1570 but returned a final time in 1572. Knox was described by his clerk, Richard Bannatyne, as "the light of Scotland, the comfort of the Church ... the mirror of godliness, and pattern and example to all true ministers, in purity of life, soundness of doctrine, and boldness in reproving of wickedness; one that cared not for the favour of men, how great soever they were." A less partial man, Principal Smeton, also spoke of Knox in glowing terms: "I know not if ever so much piety and genius were lodged in such a frail and weak body. Certain I am, that it will be difficult to find one in whom the gifts of the Holy Spirit shone so bright, to the comfort of the Church of Scotland. None spared himself less in enduring fatigues, bodily and mental; none was more intent on discharging the duties of the province assigned to him. ... Released from a body exhausted in Christian warfare, and translated to a blessed rest, where he has obtained the sweet reward of his labours, he now triumphs with Christ." Archibald Campbell, First Marquess and Eighth Earl of Argyll (1607-1661) - When religious principle came into question, titles, lands, and power meant nothing to Campbell. Firmly believing that Christ, and not the king, was sovereign over the church, he signed Scotland's 1638 National Covenant, a response to Charles I's attempts to rule the church in Scotland. The Covenant emphasized Scotland's loyalty to the king, insofar as the king did not infringe upon religious faith and freedom, and it declared that any move to force Catholicism on the Scottish church would be rejected. In the ensuing years, a series of failed military campaigns and political entanglements, the latter of which included a betrayal by the pretender and butcher, Oliver Cromwell, left Campbell both penniless and powerless and, finally, the defendant in a trial for conspiracy in the murder of Charles I. Though he was acquitted of the charge, his prior collaboration with the Cromwellian government gave Charles II the weapon he needed to have Campbell found guilty of treason. When a sentence of death was pronounced and Campbell's wife cried out, "The Lord will pay them back for this!" he quietly admonished her: "Control yourself, Dear. Truly, I pity them. They don't know what they are doing; they may shut me in where they please, but they cannot shut God out from me. For my part, I am as content to be here as in the castle, and as content in the castle as in the Tower of London, and as content there as when at liberty, and I hope to be as content on the scaffold as any of them all." Archibald Campbell, Covenanter, stood on the scaffold on 27 May 1661 and spoke calmly to those around him. A physician checked his pulse and found it steady. And then, he was beheaded.

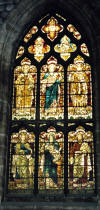

This 1834 church in Creetown was the third building for the parish. The first, built in 1645, now stands in ruins high on a hill near Fell Quarry. As we took our picture, the custodian arrived and invited us in. We admired the long wood panel and were told it had been taken from the old church building and brought to the new. The admonition carved on one inset ~ Fear God and Honowr the King ~ had guided the early Presbyterians to honor those in authority while preserving the right of Christ, not the king, to govern the Church. The last Scottish National Covenant was signed in 1684.

A Christian church has stood on this same spot in the town of Dumfries for more than 1,300 years. The present edifice was built in 1746. Rev. Patrick Linn was Minister of Dumfries from 1715 until his death in 1731. When this church was built, his tombstone was moved from its original location and placed in an outside wall of the building. It reads in part that he preached “in publick with uncommon eloquence, undaunted courage and impartial freedom to the edification of many” and was “faithfull in every relation, of a truely Christian spirit ...” St. Michael's was also the home church of Robert Burns and is his burial place. His remains have been moved to a prominent corner of the kirkyard and placed in a mausoleum, which unfortunately we failed to photograph.

In the village of Durisdeer, on the western edge of the Lowther Hills in Dumfriesshire, is this fine stone kirk built by the first Duke of Queensberry in the late 17th century. More images of Durisdeer can be seen at http://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/durisdeer/durisdeer/index.html.

Lord Cromwell, who earlier had pretended to sympathize with the Covenanters, now viciously opposed them. He placed his army in the kirkyard and made it a prison. In 1679, about 1,200 Covenanters were confined in the open air with only water and four ounces of bread each day. Many died while others were either executed, sent abroad as slaves, or freed upon signing an oath of allegiance. Over the course of the entire Presbyterian struggle, 30,000 Scots died for their faith.

This church was built on the north shore of Loch Awe over a period of about 50 years beginning in 1881. The area was largely deserted until the late 1870s, when the Callander and Oban Railway opened. One Walter Campbell then bought the island of Innis Chonain on Loch Awe, and built a house for himself, his sister Helen, and their mother, Roline Agnes Campbell of Blytheswood. Since the nearest church was too far for the elderly Mrs. Campbell to travel to, Walter built St. Conan's Kirk on the north shore of the loch. Initial construction was completed in 1886. After his mother's death in 1897, Walter decided to expand and embellish the building considerably. Then, from Walter's death in 1914 until her own in 1927, Helen continued the work her brother had begun. It was completed finally by trustees, and the present church opened for worship in 1930. The architecture is an interesting, lovely, but sometimes strange mix of various periods and styles of church architecture. More images can be seen at http://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/lochawe/stconans/.

The oldest religious structure we visited in Scotland was this abbey in Ayrshire. As establishments of the Roman Catholic Church, abbeys included not only a church but also a gatehouse (full-size photo above), a chapter house for the friars, a treasury, a kitchen and dining hall, an inner court - which here centered around a well, a residence for the abbott - in this case a tower house, and apartments for both retired abbots and patrons no longer able to live independently. At Crossraguel, the apartments were adjacent to the abbott's tower house. Crossraguel was built in 1244 and was badly damaged by the English less than a century later because of its loyalty to Robert the Bruce. It was rebuilt but eventually fell into ruin.

Copyright 2018 · Loretta Lynn Layman · The House of Lynn

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)